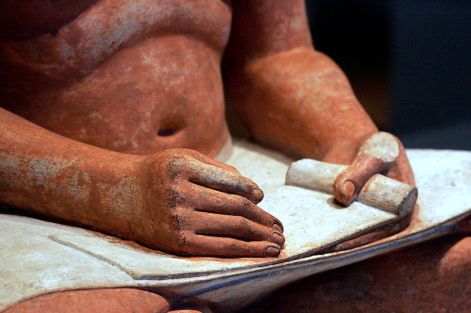

The overwhelming tendency to talk about writing systems as linguistic codes (which they usually are in some sense) has often ignored other important aspects of writing. For instance, one way way we can study writing is as a practice or action, because writing is a thing you do. At CREWS we have been particularly interested in developing the ways we look at writing practices, because this is an area with important ramifications for the way writing looks and the place of writing in a society (and in fact you can hear me speaking about some of these issues at the beginning of this seminar video).

But how can we reconstruct the ways in which writing was done, accomplished or performed in the ancient world? The nature of the act of writing is extremely dependant on a whole range of factors, from cultural attitudes and social setting to technical expertise and interactions with oral traditions. And choices about the kinds of things you write on, the kinds of things you write with and the techniques you use to ‘apply’ the writing are central to these practices. There are a number of different ways of approaching the question, one of which is by looking at ancient visual depictions of the act of writing. This is what we will focus on in this post. Continue reading “Depicting writing”