Last week the Faculty of Classics at the University of Cambridge played host to the CREWS Project’s first international conference, Understanding Relations Between Scripts II: Early Alphabets.[1] This was a wonderful opportunity for us to bring together experts on ancient writing systems from around the world and discuss each other’s research.

As with all good academic conferences, despite having a unifying theme – early alphabets – the range of papers was extremely broad. We heard about writing systems from across thousands of years of history and thousands of miles, from the earliest probable alphabetic inscriptions from the Sinai peninsula or the Egyptian desert at Wadi el-Hol, through the Phoenician and Ugaritic alphabets of the Levant, to ancient Greece, Italy and Spain. We heard from epigraphers, linguists and archaeologists, and people who stand somewhere in between.

On the first day of the conference we focused on the earliest and perhaps least familiar alphabets. In the first two papers, Silvia Ferrara of La Sapienza, Rome, and then I talked about the alphabetic cuneiform script known primarily from Ugarit, but also from elsewhere in modern Syria, Israel/Palestine, Lebanon and Cyprus. In different ways, our two papers explored the role of central authority and control in the establishment and use of the writing system, and the extent to which this was a specifically Ugaritian innovation or not. Then Ben Haring of Leiden took us even further back, to the oldest attested alphabetic writing system, so-called Proto-Sinaitic, which remains highly enigmatic and controversial. Dr Haring argued for the high antiquity of this early alphabet, with the evidence pointing to its first use during the Egyptian Middle Kingdom around 1800 BC, if not even earlier.

On the second day of the conference we turned our attention to the Phoenicians and the transmission of the alphabet to Europe. First Reinhard Lehmann of Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz led us through the earliest surviving Phoenician inscriptions – and suggested that perhaps ‘Phoenician’ is not a very helpful term in this period, when distinctions between Semitic languages such as Phoenician or Hebrew had not yet developed. He also demonstrated how well-developed calligraphy was, even in these early inscriptions, suggesting that this was hardly a new or experimental system when they were made. Roger Woodard of Buffalo University took us westwards, to ancient Greek, and argued that the representation of vowels in Archaic Greek suggested an Aramaic influence in the transmission of the alphabet, alongside the Phoenician role generally assumed.

The transmission of the alphabet westwards was also the theme of Leiden’s Willemijn Waal, who looked again at the question of when this occurred, and the age-old split between Classicists, who place the beginnings of the Greek alphabet around the 8th century BC, and Semiticists, who believe there are good reasons why it should be earlier. After her, CREWS’ own Pippa Steele looked at local alphabets used in different areas of Greece, and especially that of Crete, to shed light on how the alphabet spread and was adapted through the Aegean world. Giorgos Bourogiannis of Medelhavsmuseet, Stockholm also took up this theme, with a broad-reaching archaeological perspective on the earliest alphabets from Greece.

Our final two papers took us westwards again. First Karin Tikkanen of Uppsala told us about her work on the adaptation of the alphabet for use with the Italic languages of pre-Roman Italy, and then Coline Ruíz Darasse of Bordeaux explored the complex patchwork of writing systems in the Iberian peninsula.

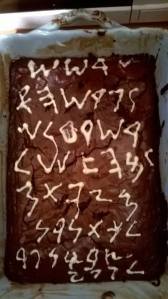

At any conference like this, though, the papers were only half the story. There was also lively and productive discussion in the questions, in tea-breaks and in the pub. In keeping with tradition for Cambridge’s Classical linguists, I made an inscription cake. This one depicts the Nora Stone, a Phoenician stele from Sardinia which is one of the earliest substantial Phoenician inscriptions in the west. This makes it an apt choice because in many ways the conference was all about relationships between writing systems – and between the people using them – that spanned the whole Mediterranean. (And it is also an inscription that fits nicely onto a rectangular cake!)

At any conference like this, though, the papers were only half the story. There was also lively and productive discussion in the questions, in tea-breaks and in the pub. In keeping with tradition for Cambridge’s Classical linguists, I made an inscription cake. This one depicts the Nora Stone, a Phoenician stele from Sardinia which is one of the earliest substantial Phoenician inscriptions in the west. This makes it an apt choice because in many ways the conference was all about relationships between writing systems – and between the people using them – that spanned the whole Mediterranean. (And it is also an inscription that fits nicely onto a rectangular cake!)

All in all, VRBS II was a great success and a lot of fun. We’re already looking forward to VRBS III in a couple of years time!

Are you wondering why the conference title Understanding Relations Between Scripts is abbreviated to VRBS? Well, the acronym spells out a Latin word, urbs, meaning “city”, which is the rationale behind the conference logo (it’s supposed to look like a little city, but each building is a letter from an early alphabet!). In the ancient Roman alphabet, however, V and U were the same letter. In majuscule (i.e. capital letters such as would be cut on stone) it looked more like a V, but in minuscule (i.e. lower case letters such as might be achieved when writing by hand with ink) it looked more like a u. So, since you tend to use capital letters when writing out an acronym, it made sense to use a V for the first letter.

~ Philip Boyes (Research Associate on the CREWS Project)

[1] Even though it’s our first conference, this is VRBS II because it follows the original Understand Relations Between Scripts conference which was held in 2015, before the CREWS Project started. The proceedings volume, edited by our Principal Investigator Pippa Steele, will be published soon.

Reblogged this on Ancient Worlds and commented:

Last week the CREWS Project held its first international conference. Read about it here!

LikeLike