In the Bronze Age, two incompatible alphabetic writing systems developed independently in Canaan—to the North, Ugarit’s alphabet had an interface derived from syllabic cuneiform and, to the South, miners in the Sinai used a hieroglyphic ideogram interface. From the outset, both of these regional scripts relied upon omission, where readers had to fill in gaps by supplying missing vowels. Also from the outset, both symbolic systems used individual graphemes to represent individual consonants. Both systems had their strengths, similar to the communications format war of the 1980s between Sony (Betamax) and JVC (VHS). If that reference seems obscure, you might compare these parallel but incompatible alphabetic technologies to the choice of Blu-ray versus HD-DVD, or Chrome versus Safari—although both performed well, only one format thrived. The cuneiform version had the benefit of deriving from a common international cuneiform system, using common clay scribal media and tools, and having the advantage of disambiguating three specific vowel combinations with the consonant ˀalp (ˀa, ˀi, ˀu). This Ugaritic version would play the part of Betamax in our analogy, a version with a bit more precision but perhaps not as accessible.

Continue reading “Mind the Gap: Abbreviations, Contractions and Alphabetic Symbolism: Guest post by Brien Garnand”Dots between words in Northwest Semitic inscriptions

Semitic writing systems, such as those used for writing Hebrew, Aramaic, Ugaritic and Phoenician, are well known for the fact that signs for vowels are routinely left out. Have a look at the first line of the first book of the Bible, Genesis 1.1 (text taken from https://tanach.us/ with the vowels and cantillation signs removed), the so-called ‘consonantal’ text:

בראשית ברא אלהים את השמים ואת הארץ

This is how this verse would have appeared in antiquity. The vowel points and cantillation marks that we find in Hebrew Bibles today came in in the medieval period (https://tanach.us/):

בְּרֵאשִׁ֖ית בָּרָ֣א אֱלֹהִ֑ים אֵ֥ת הַשָּׁמַ֖יִם וְאֵ֥ת הָאָֽרֶץ׃

As the following transcription of the consonantal text shows, most of the letters correspond to consonants, and the vowels are largely unwritten (the main exception being the /ī/ vowel in rˀšyt = /rēšīt/ “beginning”):

brˀšyt brˀ ˀt ˀlhym hšmym wˀt hˀrṣ

Greek is famous for having taken a Northwest Semitic alphabet and introduced regular vowel writing (see for example Sampson 2015, 104–105). There is some evidence for believing that Greek may not have been the first writing system to introduce regular vowel writing—this honour may belong to Phrygian (see Waal 2020, 114). At any rate, at least from a typological point of view, it is clear that Greek (and Phrygian) writing differs from Northwest Semitic in that if a vowel appears in the spoken language, you have to write it down; in Northwest Semitic, you don’t have to.

Continue reading “Dots between words in Northwest Semitic inscriptions”Animating the Alphabet – in Lego!

Today is International Lego Classics Day on Twitter, an annual occasion when classicists all over the world dive into their Lego collections to build models related to their research. We’re big Lego fans here at CREWS and every year we try and do a couple of things for ILCD. As this year will be the last when the Project is running, we wanted to pull out all the stops. This is the result, a short film telling the history of alphabetic writing through the medium of Lego stop-motion.

I’ve wanted to try my hand at a CREWS-related stop-motion video for a while but the timing has never worked out. Fortunately this year I had just sent off proofs for two forthcoming CREWS publications so had enough leeway in my diary to get stuck in to a little Lego project for a few days.

Continue reading “Animating the Alphabet – in Lego!”Elven Vowels II

In a previous post for the CREWS blog, I explored the way in which vowel signs are used in the Tengwar to write various Elven languages. In this post, I want to focus on the question of the way in which vowel writing develops, as envisaged in Tolkien’s Legendarium.

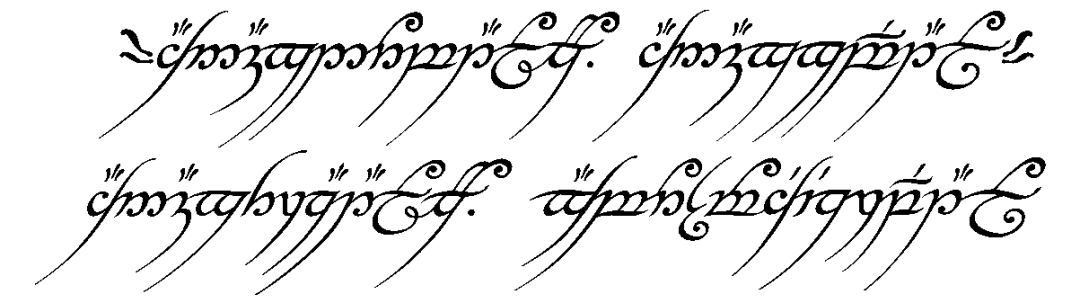

According to Tolkien, by the Third Age, that is, the period described in The Lord of the Rings, the Elven scripts “had reached the stage of full alphabetic development, but older modes in which only the consonants were denoted by full letters were still in use” (Appendix E II). In other words, in the universe of The Lord of the Rings, contemporary scripts write vowels like any other letter, but archaic scripts continued to write vowels above and below the consonantal letters, using marks known as tehtar. We see the former approach in use in the inscription on the West-gate of Moria, while we see the latter on the ring inscription. The difference is plainly visible in the relative lack of markings above the letters in the West-gate inscription.

pedo mellon a minno

“Speak friend and enter”

Section of West-gate inscription (Typeset using the TengwarScript package in LaTeX, https://ctan.org/pkg/tengwarscript?lang=en, using the Tengwar Annatar font designed by Johan Winge)

Ash nazg durbatulûk, ash nazg gimbatul,

Ash nazg thrakatulûk agh burzum-ishi krimpatul.

“One ring to rule them all, one ring to find them. One ring to bring them all, and in the darkness bind them.”

Ring Inscription (image from here).

Tolkien and Elvish Writing

Today is the 65th anniversary of the publication of The Fellowship of the Ring, the first part of JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy. To celebrate, we’re going to have a look at Elvish writing and its remarkably analytical structure: the Tengwar signs provide a very close fit for the sounds of the Elvish languages, which is unusual among the world’s ‘real’ writing systems.

The languages invented by JRR Tolkien are at the centre of his tales of Middle Earth, occasionally quoted directly but ever-present too in the names of places and people throughout his stories. Along with the languages, he created a number of writing systems to go with them, fleshing out the linguistic and cultural practices of the characters he had invented, and constructing a complex linguistic history for Middle Earth that was reflected also in script developments. Continue reading “Tolkien and Elvish Writing”

Exploring the social and cultural contexts of historic writing systems: the CREWS conference

The second of our three big CREWS project conferences took place recently: Exploring the Social and Cultural Contexts of Historic Writing Systems (14th-16th March 2019, see here for programme). I had been excited about it for a long time, but when it came I was absolutely blown away by the quality of the presentations and the new things I learned and the ways it has developed my thinking on writing practices. I’m going to use this blog post to try to pass on some of what I learned by telling you about themes that kept turning up over the three days, even in papers on completely different topics.

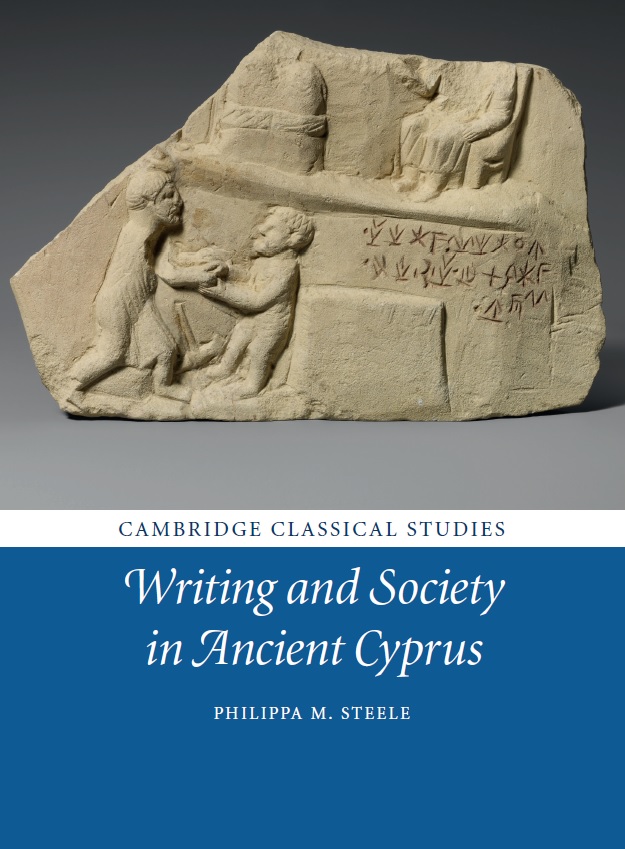

Writing and Society in Ancient Cyprus – Pippa’s new book

A couple of months ago my new book, Writing and Society in Ancient Cyprus, was published with Cambridge University Press. This was a long-term project, beginning with a series of lectures given at All Souls College, Oxford, in 2014 and culminating in a work that underpins the research undertaken at CREWS. In fact, it was in writing this book that the whole idea for the CREWS project began…

Please note that you can now read the first chapter for free with open access HERE.

Continue reading “Writing and Society in Ancient Cyprus – Pippa’s new book”

Indiana Jones and the Ancient Inscriptions

When I was little, I wanted to be Indiana Jones. I grew up on those films, and archaeology was the first profession I dreamed of. The more I watched them, the more I was drawn to some particular scenes that involve pieces of writing – looking back, it feels as though my career began when I became curious about how to become someone who could look at an ancient inscription and work out what it meant.

In the world of Indiana Jones, being able to read an inscription tends to be linked with cracking codes and solving mysteries. In some ways, that is what I do for a living now (how lucky am I?) – although not usually in life-or-death situations or while being chased by Nazis. Continue reading “Indiana Jones and the Ancient Inscriptions”

Writing in Carthage: the Punic Script

One of the topics that I have been working on a lot this year has been the development of the Punic script. This was the script used to write the variety of the Phoenician language spoken in the Western Mediterranean in the second half of the first millennium BC through to the early first millennium AD. It is descended from the Phoenician script, which was modified from an early alphabetic script to write the Phoenician language in the late second millennium BC.

The Punic language is perhaps not that widely known among languages in the ancient world. However, its speakers, the Carthaginians, including among their number the general Hannibal who famously took his elephants over the Alps to attack the Romans, are.

Hannibal’s celebrated feat in crossing the Alps with war elephants passed into European legend: detail of a fresco by Jacopo Ripanda, ca. 1510, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Image from HERE. Continue reading “Writing in Carthage: the Punic Script”

CREWS Display: A Phoenician Arrowhead

Today in our survey of the objects in the CREWS exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum, we’re looking at this bronze Phoenician arrowhead, on loan from the British Museum.