I am delighted to announce the outcome of the third and final round of the CREWS Visiting Fellowship, which will see a further three scholars coming to spend time with us here in Cambridge working on ancient writing systems. The Covid-19 pandemic has caused some delays with our fellowship programme, and there is sadly still some uncertainty about when Visiting Fellows from our second and third rounds will be with us – but we are very much looking forward to welcoming them when circumstances allow. In the meantime, you can read a bit more about the new fellows and their research below. Featuring ancient Byblos, Old Phrygian and machine-learning tools for restoring Greek, Latin and other inscriptions!

Michel de Vreeze (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden)

Michel de Vreeze (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden)

Michel de Vreeze is a Near Eastern archaeologist working foremost on Bronze Age societies. He is currently working as a project-curator on a planned Byblos exhibition at the Rijksmuseum of Antiquities in Leiden. He has a longstanding interest in early (alphabetic) scripts and the role they play in society. One of his ongoing interests are the enigmatic Late Bronze Age Deir ‘Alla tablets that were found in Jordan, recently arguing they represent a unique form of Canaanite writing and most likely associated with cultic activities (MAARAV 23.2 (2019): 443–491).

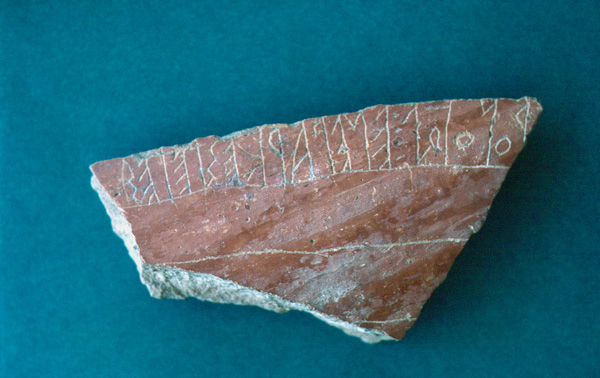

During the visiting fellowship he will further contextualise the various scripts used at Bronze Age Byblos within the wider research framework of early (alphabetic) script. This coastal town had a long and intriguing relationship with ancient scripts and is primarily known for early Iron Age attestations of the alphabet. Byblos shows a very particular cultural trajectory based on millennia of closely interlinked contact with Egypt. This must have included scribal contacts at a very early stage of its history, and at a still unknown point of time developed into the use of a still undeciphered syllabary script (which we call pseudo-hieroglyphic).

In considering this script and its role, the archaeological context (although it is problematic) is still not taken into full account. By scrutinising the contextual evidence of these objects bearing syllabary script, but also crucially combining it with other scriptural and non-scriptural related artefacts and their contexts it might be possible to get a better understanding of the various roles writing played at Byblos. Very much like Ugarit, the site must have yielded writing in different cultural settings, as well as scribes versatile in various scripts, at Byblos including hieroglyphic/hieratic and cuneiform, but rapidly expanding in script forms. It might also help us to understand the eventual adoption of the alphabet and how it came to replace other forms of writing.

Rotislav Oreshko (Leiden University Centre for Linguistics (LUCL) /

Rotislav Oreshko (Leiden University Centre for Linguistics (LUCL) /

Centre for Hellenic Studies (Harvard University))

The research area of Rostislav Oreshko embraces Anatolia, the Aegean and the Balkans in the 2nd and early 1st millenniums BC, and he is especially interested in the ethnolinguistic and sociolinguistic history of the region, migrations, onomastics, as well as linguistic and cultural contact. He completed his PhD thesis, dedicated to the analysis of the early Hieroglyphic Luwian inscription SÜDBURG, in 2012 at the Free University of Berlin. After that he carried out postdoctoral projects at the University of Hamburg (2013-2016) and the University of Warsaw (2016-2018), primarily focusing on the peoples of western Anatolia (Lycians, Lydians, Trojans etc.) and the reflection of ethnolinguistic realities of Anatolia in the Homeric tradition. Since 2016 he is a Visiting Fellow in Homeric Studies of the Center of Hellenic Studies of Harvard University (Washington, DC) and is working at present as a Guest Researcher at Leiden University Center for Linguistics on the problem of the Balkan migrations to Anatolia and especially on the language and culture of the Phrygians.

During his stay in Cambridge he will concentrate on the paleography and dating of the Old Phrygian inscriptions, which in part builds on the incentives and results of his work on the Phrygian graffiti in 2019 in collaboration with the Gordion Excavation Project (University of Pennsylvania). The largely unexplored question of Phrygian paleography is both interesting and important, as it bears both on the problem of precise dating of the Phrygian monuments – as, for instance, the famous Midas Monument, whose dating ‘oscillates’ between the 8th and 6th centuries BC – and on the more general question of the early history of alphabet in the Eastern Mediterranean.

More specifically, he will concentrate on the three following questions connected with the earliest phases of the Phrygian alphabet: 1) identification of the earliest Phrygian graffiti and establishing its paleographical characteristics; 2) definition of the precise phonetic value of several rare letters of the Phrygian alphabet (↑, Ψ and the c-like letter) and their regional context; 3) origin, chronological distribution and paleographic development of the letter Y in central and north-west Phrygian alphabets.

More specifically, he will concentrate on the three following questions connected with the earliest phases of the Phrygian alphabet: 1) identification of the earliest Phrygian graffiti and establishing its paleographical characteristics; 2) definition of the precise phonetic value of several rare letters of the Phrygian alphabet (↑, Ψ and the c-like letter) and their regional context; 3) origin, chronological distribution and paleographic development of the letter Y in central and north-west Phrygian alphabets.

Thea Sommerschield (University of Oxford)

Thea Sommerschield (University of Oxford)

Thea Sommerschield is a finishing DPhil student in Ancient History at the University of Oxford. Earlier this year she was the Ralegh Radford Rome Awardee at the British School at Rome, and she has been awarded Visiting Fellowships at the Center for Epigraphical and Palaeographical Studies at Ohio State University and at the Centre for Ancient Cultural Heritage and Environment (CACHE) at Macquarie University. She will be a Visiting Fellow at CREWS to carry out research in the field Digital Epigraphy, exploring how Machine Learning can enable large-scale, in-depth interpretation of the epigraphic cultures of the ancient Mediterranean.

Her doctoral thesis researched how the migrant and indigenous communities settled in western Sicily adopted and adapted their socio-cultural identities during the Archaic and Classical periods. Inscriptions written in Greek, Latin and Phoenician were among the main sources of evidence for her thesis, ranging from the tophet inscriptions in Mozia to the curse tablets of Selinunte. Alongside her doctorate, Thea has studied how the study of ancient epigraphic cultures can be assisted by digital resources and computational techniques. Specifically, she has researched how Machine Learning, a field of Artificial Intelligence, can assist and extend the scope of the historian’s work on epigraphic documents.

In her most recent work, Thea has co-directed a research project developing a deep learning model for the automatic restoration of Greek inscriptions. The model, called PYTHIA, is the first ancient text restoration model that recovers missing characters from a damaged text input using deep neural networks. Bringing together the disciplines of ancient history and deep learning, this research offers a fully automated aid to the epigraphic restoration of fragmentary inscriptions, providing ancient historians with multiple textual restorations, as well as the confidence level for each hypothesis. The model’s architecture works at both the character- and word-level, thereby effectively handling long-term context information, while dealing efficiently with incomplete word representations. This makes the model applicable to all disciplines dealing with ancient texts (philology, papyrology, codicology) and applies to any language (ancient or modern).

More recently, Thea has started working on PYTHIA for Latin restoration, and is researching how metadata (geographical and chronological) can be used as additional input to condition PYTHIA’s predictions. Her future steps envision an expansion of the project to other languages (such as Sanskrit), to diverse ancient textual media (such as papyri), and to tackle different questions within the study of Ancient History. Thea will be bringing this research forward during her Visiting Fellowship at CREWS.