My research has taken a fun turn towards practical experiments lately, as some of our Twitter followers may have noticed. It isn’t just because I wanted to get away from the computer (though I did…); it’s because I have been working on a problem where direct evidence is scarce and/or difficult to interpret, and where experimentation is surprisingly elucidating.

We know that during the Bronze Age a number of civilisations around the eastern Mediterranean were using clay to write on. From Mesopotamian cuneiform to Linear A and B in the Aegean, people found that this reusable natural resource provided a vital tool for making records. But they didn’t all use it in the same way, and they didn’t all use the same implements or methods to write on it – instead traditions of writing display considerable regional differences, whether or not there might have been any influences from one place to another.

In the Near East, we do have some advantages evidence-wise: although the reed stylus used to make cuneiform wedges was by nature perishable and does not survive antiquity, there is quite a lot of documentation about it. We have a good idea how the stylus was cut from a reed, how it was held in the hand and how it was used to make impressions in clay – though even then it is by observation and experimentation that recent advances have been made. Some elucidating articles have been published online, on the Cuneiform Digital Library website, by Michele Cammarosano and Armando Bramanti, which I would recommend.

I’m not a cuneiformist, so I won’t dwell too long on the cuneiform stylus in this post. However, I think it is telling that there is still some debate as to whether cuneiform styli were three-sided or four-sided – something Philip has talked about before. Iconographic representations of styli don’t help very much because they don’t show the wedge end well, but palaeographic studies looking very closely at the shapes of wedges can tell us a lot. In fact, it has been convincingly demonstrated by John Ellison that Ugaritic cuneiform was written using a four-sided stylus (see his article in THIS volume) and required minimal rotating and angling of the stylus to produce the whole range of signs of the script. Crucially, it is entirely possible that people in different places wrote cuneiform in different ways and with different-shaped implements.

If it sounds challenging trying to recover the nature of the cuneiform stylus, things are twice as difficult if we turn to the Bronze Age Aegean. We have almost no direct evidence for the styli used to write Linear A and B, other than the tablets themselves. Every stroke preserved on the tablets bears the impression of the stylus used to make it.

For Linear A and Linear B on Crete at least, we can be pretty certain that tablets were incised with a very sharp tool that was dragged through the surface of the clay to make each stroke of a sign. From experiments I can tell you that this really does require a *very* sharply pointed stylus, otherwise you get a great deal of clay thrown up at the side of every stroke. The real tablets do feature this ‘throw-up’ (which is how we know that the point of the stylus was dragged through the clay), but only to a degree. The tablet above is a nice example that shows where deeper incisions lifted more clay than shallower ones.

There has been some suggestion (as published by John Chadwick in his Mycenaean World book for instance) that a thorn might have been used to make such incisions. That seemed hard to believe, but when we had a Linear A clay playday a couple of years ago, we found that an acacia thorn made a perfect writing implement (and was much bigger than I had expected – see the picture to the right). It far surpassed the bamboo skewers we were using, which threw up so much clay that it was hard to make the signs distinct (see the bit of tablet to bottom-left here!).

There has been some suggestion (as published by John Chadwick in his Mycenaean World book for instance) that a thorn might have been used to make such incisions. That seemed hard to believe, but when we had a Linear A clay playday a couple of years ago, we found that an acacia thorn made a perfect writing implement (and was much bigger than I had expected – see the picture to the right). It far surpassed the bamboo skewers we were using, which threw up so much clay that it was hard to make the signs distinct (see the bit of tablet to bottom-left here!).

Now we often say that the Linear B documents found at different Mycenaean sites, which were spread across Crete and the mainland as far north as Thessaly, are remarkably similar. They use the same script, the same basic shapes and formatting, the same transactional terms and ideograms for commodities. But sign shapes can look a bit different, and it would not be surprising if methods of inscription could vary too.

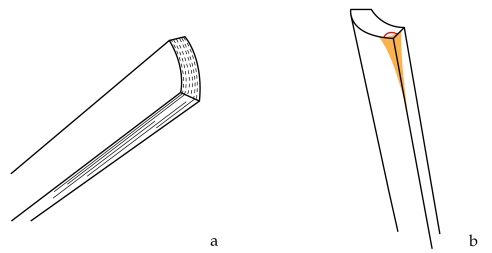

In fact, the scholar Louis Godart suggested that some flat-edged bone tools discovered at Tiryns, a Mycenaean site in the Argolid of the Peloponnese, may have been used as styli. These implements are very different in shape from the pointed thorn-like styli that seem to have been used in Crete, but experimentation suggested that they could be used effectively to write Linear B – and indeed I found the same in my own experiments, using a plastic knife cut to the right shape and proportions (it turns out plastic is a good substitute for ivory because it is both thin and hard). You can see the ends of some of my styli above.

My most recent experiments actually focused on Bronze Age clay tablets from Cyprus, which are in a writing system we call ‘Cypro-Minoan’, related closely to Linear A. Here we not only have no direct evidence of styli, we also have very varied traditions of writing that suggest varied methods too! Playing around with different types, I found that different objects often called for a different stylus, and the preserved sign impressions gave a very good idea what the shape of the original stylus was.

I still have a lot of thinking to do about how to interpret my findings – in fact, Philip and I are working on a joint article on this subject, so before long we’ll be able to update you! For now I just wanted to emphasise two things:

Firstly, there is a lot we don’t know about writing in the ancient world. You can’t just go and watch someone writing, and the evidence we have for writing methods is often indirect – we can examine the surviving products of writing but to study the act of writing involves reconstruction.

Secondly, practical experiments have a great deal to teach us. I really didn’t understand what the physical dimension of writing on a clay tablet was like until I first tried it, and not everything was what I expected! Recently I think I have been approaching a much closer understanding of how different writing traditions might have interacted, influenced and shared features with each other. But that will be the subject of a future post…

~ Pippa Steele (Principal Investigator of the CREWS project)

Reblogged this on Ritaroberts's Blog.

LikeLike