Punic is the name we give to a language spoken in north Africa, a continuation of the earlier Phoenician language (originating in the Levant, around modern Syria and Lebanon), and written for the most part in a developed form of the same writing system. Punic inscriptions have surfaced in several areas around the Mediterranean, but one of the furthest-flung examples comes from a less exotic location – Holt, a town on the Welsh border, a bit to the south of Chester. So what was Punic doing there?

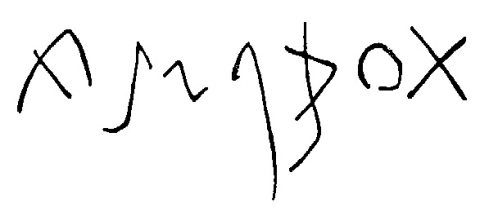

Image from A. Guillaume ‘The Phoenician Graffito in the Holt Collection of the National Museum of Wales’, Iraq 7 (1940), 67-8.

Well, the inscription is on a piece of pottery, found at a Roman site associated with ceramic production. It is likely that the site in turn had a close relationship with the nearby Roman fort and town at Chester, known then as Deva. The pottery sherd is difficult to date – somewhere between the 1st and 3rd century AD, at a guess.

Roman tile stamped with a Roman inscription: Leg[io] XX (the 20th Legion). One of many Roman inscriptions to be found in Chester’s Grosvenor Museum.

It is not too difficult to envisage a scenario in which a speaker of the Punic language might have been living in this area in this period. He may have been a soldier, or attached to the Roman army in some other way. It is difficult to tell the extent of this individual’s literacy, for example to extent to which he was proficient in writing in Punic, or whether he might also have been able to write in Latin. But at the very least he was able to write his own name in the Punic alphabet.

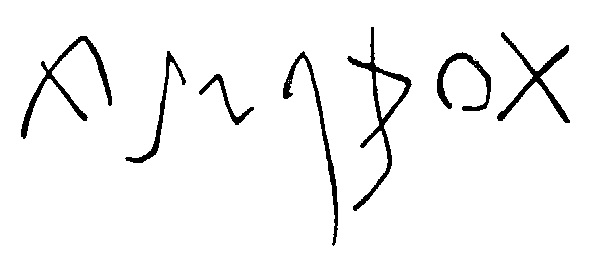

Drawing of the Punic inscription from Holt: Karl Jongeling, http://www.punic.co.uk/phoenician/neopunic-inscr/nptxts/walesframes.html.

The inscription reads from right to left, as always in Phoenician and Punic: MᶜQRYNᵓ. This is a name that occurs in some north African inscriptions too, and seems to spell out a Roman name, Macrinus. Although the writing system is a consonantal alphabet, i.e. one that did not originally have dedicated signs for vowels, here we can see that matres lectionis (i.e. redeployed consonant signs) are used to represent the vowels in the name: the ayin (circular sign, second from right, usually a pharyngeal consonant) is used for the A, the yod (small Z-shaped squiggle, third from the left, usually a Y as in ‘yet’) is used for a long I and the aleph at the end (the left-most sign, usually a glottal consonant) represents the vowel at the end of the word (final aleph is often used to render Latin names with -us endings). The problem of denoting vowels in writing is something that Rob is looking at in his CREWS research, as he has mentioned previously on the blog.

Cypriot bilingual inscription where a man named Menahem son of Benhodesh in the Phoenician half is called Mnases son of Nomenios in the Greek half. Trustees of the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=366074&partId=1&searchText=cyprus+bilingual+inscription&page=1.

It may seem strange that this Punic writer/speaker had a Roman name, but the popularity of the name Macrinus in north Africa might actually suggest that Macrinus was similar to a name in a local language – perhaps something like Makar. ‘Translating’ names was quite a common phenomenon in the ancient world, and something I have worked on in the past in relation to ancient Cyprus (where bilingual inscriptions sometimes show an individual using a Phoenician name while writing in Phoenician but a Greek name while writing in Greek).

So perhaps we should not be very surprised to find an author of a Punic inscription living in Wales and using a Roman name. This is really just a symptom of a very interconnected ancient world – no less so than today!

If you found this interesting, why not have a go at writing your own name in the Phoenician alphabet with our ‘write your name’ sheet – this is an earlier form of the same script used to write Punic.

~ Pippa Steele (Principal Investigator of the CREWS project)

This is so interesting as I lived on the Welsh borders before moving to Crete

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I grew up in Lancashire, so this area (especially Chester) was always within day trip distance for me. But I never knew about the Punic inscription until I moved down to Cambridge sadly!

– Pippa

LikeLike

I knew of the inscription but did not realize it was Punic. Love Crews Project by the way. especially as I said, I am studying Linear B

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Pippa. This is very interesting. I have heard about Punic connections to Cornwall where the tin mines were (to mix with Cypriot copper to make bronze), but not this far north. Can you explain the convention you are using to transcribe the name into English/Latin letters? MᶜQRYNᵓ

I am not familiar with the small circle symbols between the latin letters.

Dave.

LikeLike

Thank you Dave! My assumption when I first heard about the Punic inscription from Wales was that it might have been related to trade (must be a Cyprologist’s assumption!), but when I looked into it, it seemed that a local soldier was much more likely.

The transcription system is the typical one for representing any Phoenician/Punic but it’s a bit hard to render in the main font used on the blog. So:

M = mem /m/

ᶜ = ayin (here used for /a/) – the usual transcription is like an opening single smart quote / backwards apostrophe

Q = qaph

R = resh

Y = yod (here used for long /i/)

N = nun

ᵓ = aleph (here used for the word ending ~ -us) – the usual transcription is like a closing single smart quote / normal apostrophe

– Pippa

LikeLike

X sign denotes tav in most versions of this Semitic alphabet. How do we get to mem (normally represented by something like a horizontal “m” with a downstroke on the right side)?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good question. Being mostly familiar with much earlier material, Ii was intrigued by the reading too, but apparently this shape for mem is common for this period (it’s pretty late even for Punic), and taw wouldn’t have the cross-shape. I was trying to find the alphabet laid out somewhere but this is the best I can find right now: https://www.omniglot.com/writing/punic.htm

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Die Goldene Landschaft.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on sideshowtog.

LikeLike