We’ve talked in the past about the Linear B and Greek alphabetic script in the first two lines of the CREWS logo. Today we’re going to skip ahead and have a look at the last line. This is written in Ugaritic alphabetic cuneiform.

Ugarit was a city on the coast of what’s now northern Syria, not far from the Turkish border. The site was occupied since the Neolithic period, but it’s the Late Bronze Age city of the end of the second millennium BC that we know most about and which has really captured the attention of scholars. In that period, up until its destruction in the early 12th century BC, Ugarit was a major trading hub, involved in commercial and diplomatic networks stretching from the Aegean to Mesopotamia and beyond. When archaeologists began excavating the site in the early 20th century, as well as texts in several of the known languages of the period, they found numerous clay tablets in an unknown script.

This was a type of writing known as cuneiform, from the Latin for ‘wedge-shaped’, since it was comprised of wedge-shaped indentations pressed into soft clay. Cuneiform writing systems are well-known in the Near East. Initially used for writing Sumerian, the method was later adapted for Akkadian, the language of Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) which came to be used as a general lingua franca for trade and diplomacy across much of the ancient world. Standard Akkadian cuneiform is primarily a syllabic writing system – which means that each sign can stand for a syllable – although to complicate matters it also sometimes uses the cuneiform signs logographically, to stand for the word they were used to spell in Sumerian, even if they aren’t used to spell it in Akkadian.

So, for example, the sign:

in Akkadian can stand for any of the syllables gis, gish, giṣ, giz, is, iz or iṣ; but it can also be used logographically to stand for the Sumerian word isu – wood, and so can also be used as a modifier (known as a determinative) before an Akkadian word to signify that the object is made out of wood.

You may be thinking that this sounds like a rather complicated system, and you’d be right. There are hundreds of Akkadian cuneiform signs, which can have several different values each.

So let’s get back to the cuneiform found at Ugarit. The excavators immediately saw that this was something quite different. Not only were the cuneiform signs themselves different in appearance; there were also far fewer of them – only 30 in fact. They quickly worked out that this was not a syllabic writing system – the Ugaritian scribes had adapted the idea of cuneiform so that each sign (more or less) stood for only a single consonant. Although there are no proper signs for vowels, this is a system far more like the alphabets we are familiar with in the West.

Working from the assumption that the script was alphabetic, and that it was used to write a North-West Semitic language related to other Levantine languages such as Phoenician or Hebrew, decipherment of Ugaritic came very swiftly, taking only around a year and opening up to us a wealth of texts dealing with every aspect of life in the city, from diplomacy and trade to law, religion and myth. We even have the practice exercises written out by trainee scribes in the city’s numerous scribal schools, so we know how they were taught to write!

In the CREWS logo we have:

That is, krws. As you can see, unlike many other Semitic writing systems, Ugaritic is written left-to-right.

The first couple of signs are straightforward: Ugaritic ‘k’ and ‘r’ correspond fairly straightforwardly to English’s hard /k/ and /r/ sounds. If CREWS were a French project, however, we might have chosen something different – the Ugaritic sign

transcribed as ‘g’ with an acute accent represents something close to the French /r/, so a French-speaker might have used that for ‘Relations’.

There’s no sign for ‘e’ – as I said, Ugaritic doesn’t generally write vowels. However, the sharp-eyed among you may have spotted three things in the alphabet above that look suspiciously like vowels:

That little crescent before the vowel is the aleph, the sign for the glottal stop (the sound that replaces the /t/ if you say ‘bottle’ with a Cockney accent), which is the consonant which is the primary purpose of these signs. But Ugaritic writes this aleph three different ways, depending on which vowel was pronounced after it. So you could think of these as sort-of vowel signs, or as syllabic signs; either way, they’re a bit of an anomaly in the standard Ugaritic alphabetic system. A welcome one, though, since they’re one of the ways we can reconstruct what vowels speakers actually said. Regardless, there’s no sign for /e/, so we have to omit it in our logo.

Finally we have the ‘s’. As you can see, Ugaritic has no fewer than four signs transliterated using our letter ‘s’:

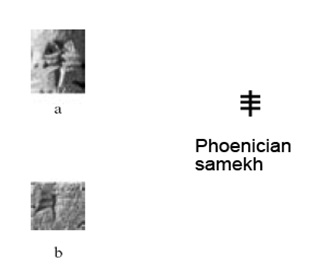

The first, š, corresponds to what English writes as ‘sh’, so clearly isn’t what we want here. The second is the standard English /s/, and that’s what we went for in our logo. So what about the other two? Ṣ probably stands for something like /ts/, but the final sign s with a grave accent is a bit more difficult. It’s very rare, even in Ugaritic, and seems to have been added to the alphabet late. It’s only used as a variant for ordinary ‘s’ in a small number of words borrowed from other languages. We don’t know for sure how it was pronounced, but something like /ts/ has been suggested for this too. One final thing that’s interesting about this letter is that of all the Ugaritic cuneiform signs, it’s the one with the clearest link to anything written in a linear script – that is, one you could write with a pen and ink.

A variant of the sign looks very similar to the Phoenician letter samekh, which may be a coincidence, or it could have interesting implications for the relationship between Ugaritic and the linear alphabetic script developing in the Levant towards the end of the second millennium BC. This is something I’ll be looking at in more detail as I research the context of the creation and use of Ugaritic.

Comparison of variant form of s̀ and Phoenican samekh. Adapted from fig. 12.12 in Pardee, 2007 –‘The Ugaritic alphabetic cuneiform writing system in the context of other alphabetic systems’

I hope you’ve enjoyed this quick introduction to Ugaritic cuneiform. I’m sure I’ll be back soon with more about writing at Ugarit. In the meantime, I’ve written a bit about my attempts to make my own Ugaritic cuneiform here and here, so have a look at those if you’re interested.

~ Philip Boyes (Research Associate, CREWS Project)

Reblogged this on Ancient Worlds and commented:

I’ve written a post over on the CREWS Project blog about the Ugaritic alphabet and how it appears in the project logo.

LikeLike