We’ve talked before on this blog about the importance of hands-on experience with inscriptions. Seeing and handling the real thing gives a much clearer idea of the practical realities of reading and writing an ancient script than working from a transcription or even a drawing or photograph.

So I was very lucky this week to be able to visit the British Museum with Cambridge’s Assyriologists, for a behind-the-scenes tour and a hands-on session with some of their many cuneiform tablets.

The day started with Dr Irving Finkel showing us some of the tablets in the Museum’s newly refurbished Mesopotamian gallery. In particular, he told us about Neo-Assyrian scholarship and the contents of Aššurbanipal’s library at Nineveh. Aššurbanipal, who ruled Assyria in the seventh century BC, had never expected to be king. As his father’s youngest son, he was trained as a priest and scholar, and this included learning to read and write. After acceding to the throne, he boasted proudly of his literacy – he claimed he could even read ancient tablets ‘from before the flood’. He’s even depicted in royal iconography with a reed stylus tucked into his belt.

Ancient tablets turned up all the time in Mesopotamia – whenever people dug into the ground or demolished an old wall. Such ancient finds fascinated people, and they would have been taken to the palace scholars to be read, especially when the king himself was such a scholar. Scribes were ready for this and we have examples of tablets showing ancient cuneiform signs alongside their Neo-Assyrian equivalents. These were also useful if scribes were asked to write in the style of their ancient forebears – archaic inscriptions being perceived as more authoritative. We would expect, then, that Aššurbanipal’s much-vaunted library of all knowledge would include ancient texts that had been brought to the palace. In fact, though, there are very few such tablets. Nor are there many new or experimental texts – almost everything is Neo-Assyrian transcriptions of Old Babylonian knowledge. For this reason Dr Finkel told us he thinks that the vast number of tablets we have from Nineveh might only be a single division of the ancient library.

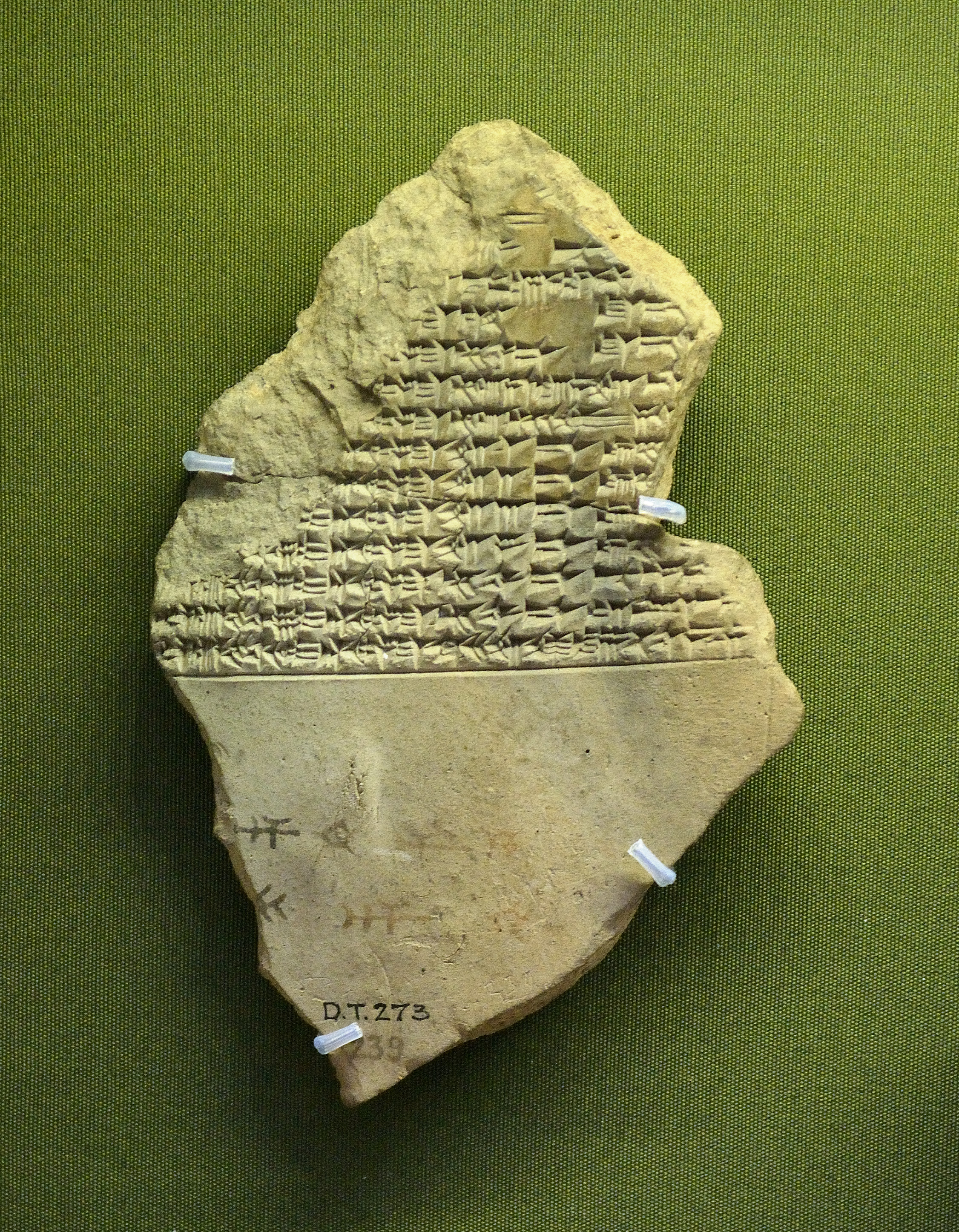

Another fascinating item Dr Finkel showed us was this fragment:

Most of the the text is impressed into the clay in the standard way, but the scribes left it too late before adding the colophon – information about the production of the text. As the clay had already dried, the information was added in ink. Dr Finkel pointed out the extreme neatness of this pen-and-ink cuneiform. Writing cuneiform in ink is no mean feat, and such neatness suggests that the scribes were extremely well-practiced in this. This is good evidence, then, that a great deal of material was written on perishable materials, not just in durable clay.

After this we went to one of the Museum’s behind-the-scenes study rooms, where Dr Jonathan Taylor got out several cuneiform tablets for us to look at and handle.

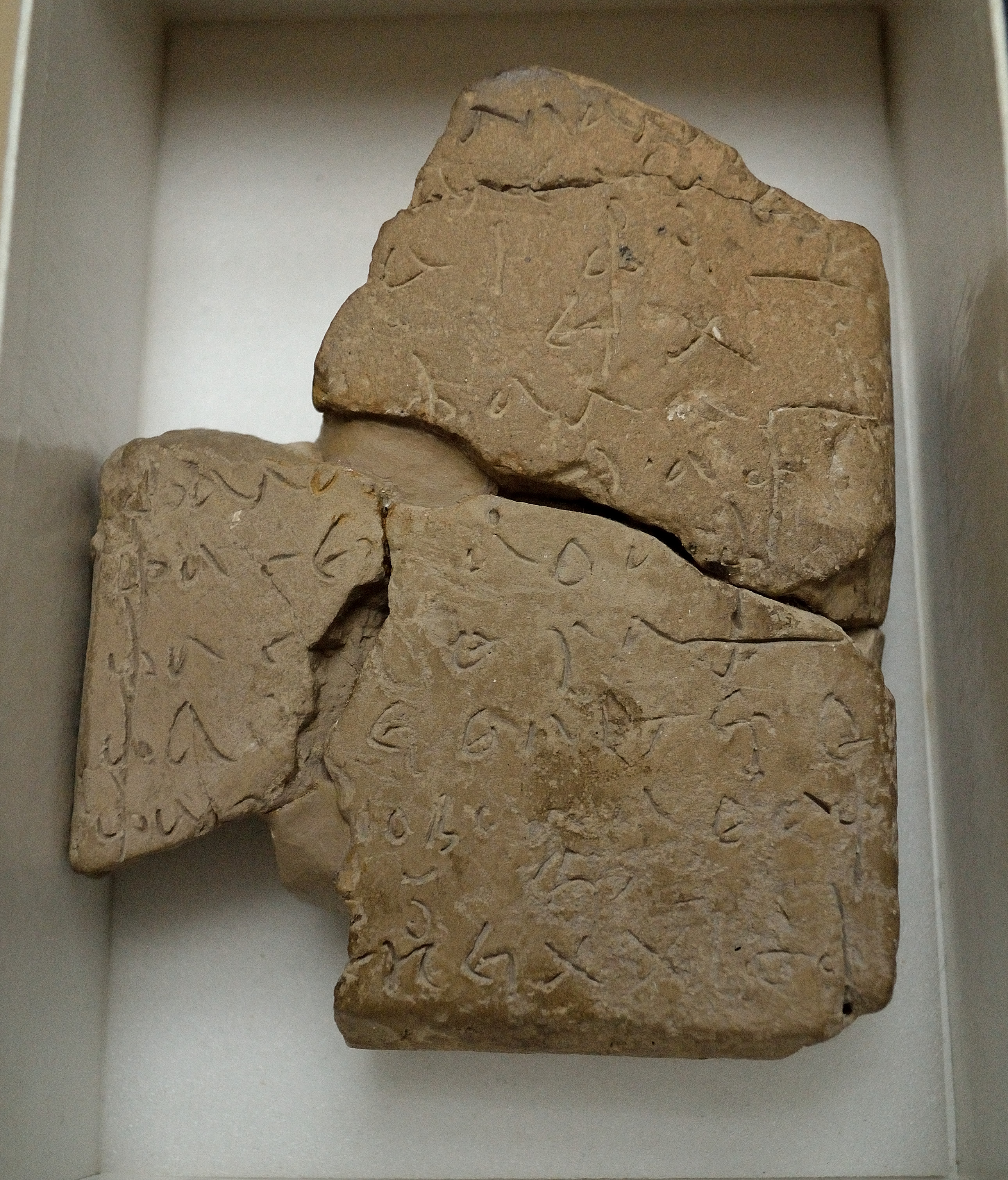

These included some fascinating examples, such as this unread letter, found still inside a clay envelope marked with the address of the intended recipient and sealed with a cylinder-seal.

There were also some nice bilingual tablets – one in Akkadian with an Aramaic label on the side, and another, late, tablet with a transcription of the Akkadian text into the Greek alphabet on the reverse.

He also showed us one of these scribal training tablets. These would have been used by very young trainees – only four to six years old. Their round shape comes from their simple manufacture – a ball of clay patted down in a child’s palm. The teacher wrote cuneiform signs on one side. The child then had to turn the tablet over and write the same signs from memory on the reverse. It’s always nice to see something of the scribal learning process.

He also showed us one of these scribal training tablets. These would have been used by very young trainees – only four to six years old. Their round shape comes from their simple manufacture – a ball of clay patted down in a child’s palm. The teacher wrote cuneiform signs on one side. The child then had to turn the tablet over and write the same signs from memory on the reverse. It’s always nice to see something of the scribal learning process.

In the afternoon we got to learn about the process of facsimile manufacture. We think of museums as showing originals, but the British Museum has always been involved in the production of high-quality replicas for study or display while originals are on loan. Mike Neilson showed us some of the replicas currently on display. In some cases they have been used to identify joins with fragments held elsewhere, such as this statue of the Egyptian general (and later pharaoh) Horemheb and his wife.

For may years it was unprovenanced and unidentified, until a fragment of clasped hands was found in the tomb of Horemheb’s wife. The fragment was cast and the replica was found to match up perfectly with the Museum’s statue. We also got to see Neilson’s workshop, where he is currently producing a replica of the Sennacherib prism for Cambridge’s Division of Archaeology.

Afterwards we got to see the conservation lab, and hear about some of the challenges in looking after the Museum’s stock of clay tablets, and some of the ways conservation methods have changed over the years.

All in all, it was an extremely interesting and worthwhile day, and I learned a lot, not just about the tablets themselves but also about how they are cared for, researched and curated in a major institution such as the British Museum.

I’m very grateful to all the staff at the British Museum who took the time to talk to us, Dr Martin Worthington for organising it, and Laure Bonner at the Division of Archaeology for some of the photos I’ve shared here.

~ Philip Boyes (CREWS Project Research Associate)

Cuneiform written in ink! That’s super exciting

LikeLike

Isn’t it?!

LikeLike

Are there any other examples or is this the only one?

LikeLike

Finkel is excellent.

How old is the unread letter – about 1700 BC?

LikeLike

Er… I’m going to have to plead forgetfulness here. I’m sure they did tell us, but we looked at a lot of tablets in rapid succession and I can’t remember exactly. The cuneiform looks relatively late to me, so I’d guess it’s a bit later than that. More like 1400 onwards; possibly even somewhere in the first millennium BC. I may be wrong, though – I’m not any kind of expert on cuneiform epigraphy.

LikeLike